Funding challenges of super-high-cost therapeutics

- March 29, 2016

Since the completion of the human genome project in 2003, researchers at the 1000 Genomes Project have sequenced over 2500 human genomes from 26 groups of people around the world; the genome of a human from around 430,000 years ago has been sequenced; and the UK plans to sequence 100,000 human genomes from NHS patients. An entire human genome can now be sequenced in just 26 hours, costing a few thousand rather than millions of dollars. Knowledge of other molecular and cellular biomarkers is also growing, and these biomarkers can be used to support the development of personalised or precision medicine, which are considered high-cost therapeutics. Using companion diagnostics, patients can be stratified into groups of patients who are more likely to respond to the treatment, or less likely to experience unpleasant or toxic side effects.

However, the development of these therapies and their associated companion diagnostics can be lengthy and complex, and the eligible populations are small, meaning high treatment costs. However, payers do recognise the value of a segmented approach, because it focuses high cost treatments on those who are likely to have better responses and allows patients who are unlikely to respond to get a more appropriate drug more quickly.

Developing precision medicine

Gene therapies, cell therapies and other personalised therapeutics are often innovative, high-tech approaches, making the process more complicated. By their very definition, precision medicines are designed for a very small, targeted market, so recruiting patients for clinical trials and then recouping costs once the therapy is approved and on the market is harder.

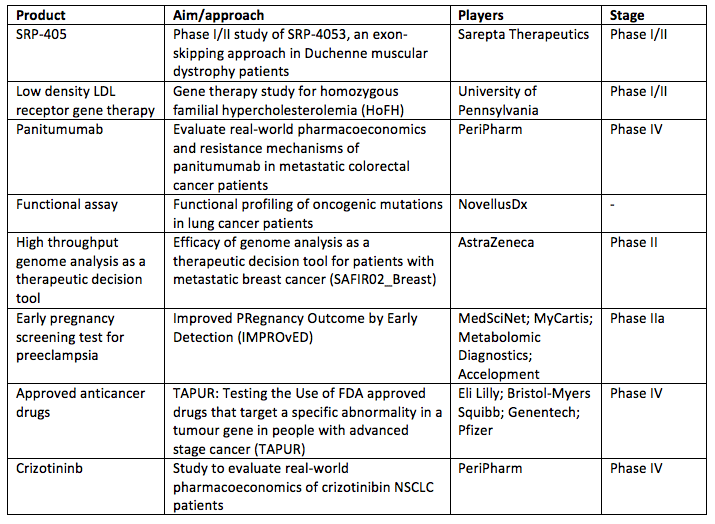

Selected examples of precision and personalised medicine approaches (both diagnostics and therapeutics) in clinical trials are given below:

Source: ClinicalTrials.gov

Because many of the precision medicine tactics are still new and many of the technologies are as yet unproven in the long term, patients have to be monitored for long periods for both efficacy and adverse effects. This level of uncertainty can make it difficult for small biotechnology companies to gain R&D funding from venture capital and may have to rely on alternative funding mechanisms, such as grants from governments, research foundations or patient alliances, or from the growing area of crowdfunding. The production costs are also high, and there is no economy of scale when developing a product for a small market.

The challenge to the payer

UniQure’s alipogene tiparvovec (Glybera) is the first licensed gene therapy, developed to treat lipoprotein lipase deficiency, a hard-to-treat ultra-rare disease with a population of only 150-200 patients in the EU. Glybera received orphan drug designation in Europe in 2004, and was approved in Europe in 2012 under ‘exceptional circumstances’, with a requirement for post-treatment monitoring of patients. Treatment per patient will cost around €1.1 million, as revealed when UniQure and its marketing partner filed a pricing dossier in Germany in November 2014.

In April 2015, the German Federal Joint Commission (G-BA) postponed their review because of concerns of lack of efficacy from the rapporteur at the European Medicine’s Agency (EMA). The reassessment in May 2015 described the benefits as ‘non-quantifiable’, and a new assessment is due to begin in June 2016. The company has decided not to pursue approval in the US, following the FDA’s requirement for a second phase III trial.

It is up to individual ‘sick funds’ in Germany to decide whether to pay for the therapeutic, which needs to be administered in hospital under a spinal anaesthetic. There are estimated to be between 17 and 35 eligible patients in Germany, and so far only two have been treated to date, which is likely to be down to the cost and the lack of appropriate payment models.

While the health impacts of innovative approaches like gene therapy, cell therapy, and other high-tech therapeutics are intended to provide benefits to patients, and bring a high value to healthcare because they can provide long term cost benefits, and even cost savings. According to UniQure CEO Jorn Aldag in a telephone interview with Bloomberg, ‘the cost [of Glybera] should be compared with other orphan drugs that target rare diseases, which on average cost about $250,000 a year’. As a clinical trial of Glybera showed efficacy over six years, the $1 million price tag does equate to less than $170,000 a year, with benefits including limits to hospital stays and reductions in long-term complications such as heart disease and diabetes.

Finding the pricing models and improving outcomes

In most markets, medicines are paid for upfront by payers. Even though the direct and indirect costs may be considerable over a patient’s lifetime, these are spread over much longer periods than what is normally accounted for in healthcare budgets. Highly innovative and potentially curative approaches could provide wider cost-savings and socioeconomic benefits, potentially allowing individuals to continue in education, work and social activities; however, indirect costs such as these rarely feature as considerations in drug budgets. Current pricing models in healthcare require a single, upfront payment, which in this space of super-high-cost treatments would be challenging to bear for payers and providers who have annual rather than lifetime budgets. The challenge therefore is to create pricing models that can address the affordability and the ability to pay for both private and government payers. These could include annuity payments that spread the cost over a number of years, and/or a pay-for-performance risk-sharing model that looks at patient outcomes and rewards biopharma companies based on achieving these. But, with all these options healthcare would need to shift how medicines are currently paid for.

Funding super-high-cost medicines is proving challenging, at least partly because of the level of uncertainty for long-term, real-world benefits, these still very new therapeutic approaches do have potential as true game-changers, and the industry, payers and regulators need to work together to ensure that patients can reap the benefits by addressing the funding conundrum.

- 0

- 0

- 0

Leave a Reply